Maybe it began in a room at the Hotel Lenox when his wife called to say she was arriving in Paris for a belated honeymoon. Or maybe it began with a hotel room in Hong Kong when a woman called on behalf of another woman who spoke only Chinese. Or perhaps it was a friend’s letters from the Hotel Aroma during a trip to Nepal that gave him the idea that a hotel room represented life in a nutshell---food, shelter and a communication problem.

© Text, painting details and photographs copyright Wayne Miller

© Nepal text copyright Robert N. Pollock

used by permission of the writer

When you are young you are bulletproof. In preparation for travel you learn something about a foreign currency and a few words of a new language. Then you pack a bag, a passport, a camera, less money than you’ll need, something to use as a journal and you step out the door...

In a third floor room on the Rue de Suisse a man slept while

a woman lay awake. They were low on money. Wondering

whether they should leave for Rome or stay in Nice she fell

asleep to the sound of Algerians arguing in the street below.

The lepers did not invite us into their huts. Instead we took shelter from the sun under a cluster of small trees on the opposite side of a stream. The food we were given was nuoc maum, a fermented fish broth poured over rice. After a bowlful you couldn’t swallow anymore, and the smell of the fish made even breathing difficult.

Journal entries described above are dated as follows: Hotel Central, Nice 1972. Behind a hotel on TuDo Street, Saigon, 1969. Believing the words--advice from the painter Evelyn Ellwood, New York, 1984. The Hong Kong Carleton Hotel, 1969. Letters written by Robert Pollock from the Hotel Aroma, Kathmandu, Nepal, 1982. Leper colony, Hai Vanh Pass region,Viet Nam 1969. A hotel in the Isazaki-Cho section of Yokohama, 1970. Hotel Lenox, San Germain, Paris, 1979. Buddha’s birthday--in the yard near the medic barracks, Da Nang Air Base, Viet Nam, 1969. The Golden Hands, Saigon, 1969. A hotel on Humphrey Street, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 1969. A restaurant on the Saigon River, 1969. Telling war stories---a bar in a midtown Manhattan hotel, New York 1982. The Windsor Hotel, New York, 2009.

Don’t change money at Ton San Nhut, he was told, we’ll change it in town and get a better deal. An hour later they were standing behind a hotel on TuDo Street arguing over MPCs, piasters, and American green. Someone threw in a pair of bandage scissors and the deal was completed. Three days later, when he left for Da Nang, he had more money in his pocket than he’d come with.

“In English speaking countries,” she said, “You listen to the words,

you listen to what people are saying and you believe the words.

But in an Asian city, where you don’t understand the language,

you react on a gut level, closer to pure instinct, closer to the truth.”

The bus ride cost only a few dollars and it was a good way to get accustomed to the city. The tour included Kowloon, Victoria Island and the New Territories, with a stop in a walled village at Kam Tin. It finished with a meal at a cliffside hotel looking down on jetliners as they glided slowly past on their decent into the city.

We went to Sette and didn’t like the people at all. We left quickly and reached a teahouse run by a woman with the energy of four people --- four strong people. Pokhara was better. Climbed Sarangath, 5,500 feet high, with mountain streams and terraced rice fields. From the top six eagles could be seen flying below us.

Through half-closed eyes he watched the woman sitting on the edge of the bed, lost in thought, lowering her guard. Floral tattoos covered her back, blue and crimson images in the afternoon light, in a cheap hotel during a snowless winter.

Their room was in a small hotel on the Rue de l’Universite. It had salmon pink walls and a staircase leading up to a small bath with a window that gave a bather a view of the room below. He photographed her smiling through the glass. Each evening, after dinner and a few phone calls, they’d return to the room where television ended with a cartoon character climbing a tall ladder and turning off the moon.

The sun rose above the yard on Buddha’s birthday and the morning air was clear. The voices of women cackled like electricity as they circled an outdoor table arranging food and small flags and lighted candles. Then all at once, as if by instinct, they jumped back, and sharp firecracker blasts blew flags, candles and food into the air. As fragments of yellow paper settled in the sand and the smell of gunpowder hung in the air, the women surveyed the table. They seemed pleased with what they had done.

They sat quietly at the close of business. The business was called The Golden Hands. “Ask for me when you return to Saigon,” she said. “For whom shall I ask?” he replied. “Ask for number 12,” she answered.

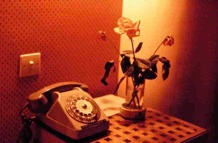

4:45 in the afternoon with faint sounds coming from the street below. The telephone rang just as he was leaving the hotel room. He stood by the door for a moment then turned, crossed the room and sat on the edge of the bed. He lifted the receiver. A woman spoke for another woman who spoke only Chinese.

In the late afternoon as the tide receded the floating restaurant began to list

to starboard. The first sign was the tendency for people to hold onto things

with both hands. By 3PM drinks were sliding into the river. Then it was time

to move to a small patio down the road where a transparent canopy bathed

the French beer in a peculiar shade of green.

“Can’t you think of anything better to do than to sit all afternoon in a hotel bar telling war stories?” she asked. He wasn’t concerned. “I’ve got no wounds,” he said,”No guilt, no nightmares. I think about Viet Nam every day and everyday the thoughts are positive.” “I don’t care if the thoughts are positive, “ she replied,” It’s been thirteen years, you’re not supposed to think about Viet Nam every day.”

They were in New York on business and took a room in a hotel in

Chinatown. They walked a few blocks west to a building on Duane

Street where they’d lived when they were first married, then walked to

Tenth Street where they’d lived for nine years in an apartment by the river. Being in the old neighborhoods reminded him of something his

father once said about World War II. “Like I read about it in a good book somewhere,” he’d said, “Like it never happened to me.”

A Room with a View